A lot of the readings we’re doing for this class touch on aesthetics – not in the classical sense where “aesthetics” equals the philosophical study of beauty and its qualities, but rather in the sense of contemporary philosophy and art history where it comes to signify the experiential perception of the world via one’s senses. In this vein, we have read and spoken of visibility and spectacle (Nixon 2011), and the hierarchy of senses (sight over hearing, in Shapiro 2015). While my arguments will remain grounded in thinking about material engagements with toxicity and the broader world, I want to take the discussion to actual art and more specifically, film, which (to me, at least) is the most beautiful, yet most toxic of art.

Film, Flames, Asbestos

Imagine a film reel – a long piece of transparent plastic base and the colorful emulsion that is printed on top of it. This is known as a film stock and it comes in a few different versions. The earliest film stock, nitrocellulose – or nitrate film, as it’s usually referred to – was extremely flammable. Auto-ignitions were also common and have led to numerous incidents, including a hospital fire in Cleveland, Ohio and the fire in Glen Cinema in Paisley, Scotland, which took the lives of 71. To prevent such disasters, many cinemas across the world installed asbestos in their projection booths.

But the abundance of asbestos in old cinema buildings (most of them remediated by now) is not the only toxic substance related to film. Developing the exposed negatives takes its toll on the filmmakers. Inhaling the fumes of volatile chemicals, used in many developers and fixants, caused respiratory issues. Indie film makers working with film today, use masks – and still sometimes cough for a month after developing film in their bathroom for a few consecutive days.

Additionally, film cleaner, used to remove dirt or oil residue from film is also quite volatile and can cause nausea and cough. Some brands of film cleaner are actually based on petrochemicals.

Nitrate film is rare today. Only two cinemas in the US are legally allowed to show it and they are banned from ever having more than two reels of film in the projection booth. Archival collections have special fireproof rooms for their nitrate films.

The decline of nitrate film usage happened long before the digital era. In the late 1940s Eastman Kodak patented a new film stock – cellulose acetate film, which came to be not as safety film and became the industry standard in the 1950 and after.

From Acetic Acid to Aliphatic Petroleum Hydrocarbon

Smell, as we’ve seen again and again (Lerner 2010, Shapiro 2015), is a powerful indicator of something wrong. This is also observable in most film archives. If you open a can of safety film, chances are it’s going to smell like vinegar.

This is because safety film is chemically unstable. While this was not recognized at the time of its invention, safety film turned out to be prone to warping, shrinking and general decay. Throughout this process of degradation, safety film emits acetic acid – which along water is one of the two ingredient of vinegar, which is why the decay of safety film is often called “vinegar syndrome”. The worst thing about vinegar syndrome is that it is contagious and unstoppable – once you have a film with vinegar syndrome, you have to isolate that film from the rest of your collection and, ideally, you’ll freeze it in order to slow down the chemical processes.

The panic around vinegar syndrome has led to some peculiar inventions. Among them is Vitafilm: a type of film cleaner whose unique selling point is that it can stop vinegar syndrome. To that purpose you have to either clean your film with it, as you would do with a regular film cleaner, or soak your film in it for three months.

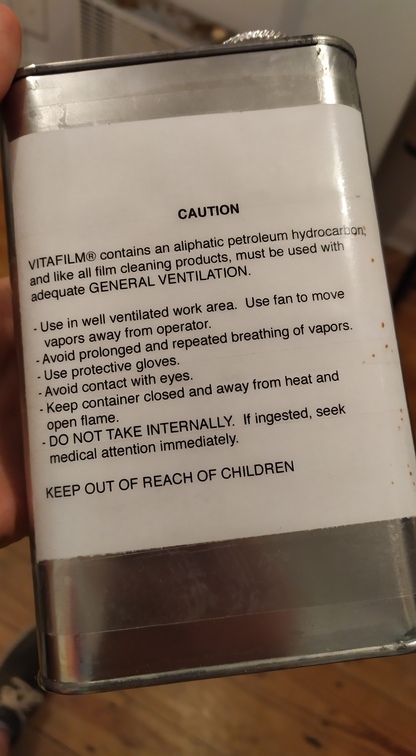

The first time I held a can of Vitafilm in my hands I was quite impressed. The back label advised caution and suggested the usage of gloves and suggested a variety of safety measures: work with mask and in a well ventilated area, avoid prolonged exposure to vapors, avoid eye contact, use protective gloves.

One of the main ingredients of Vitafilm, as pointed on the same label, is aliphatic petroleum hydrocarbon. This could mean different things – methane, acetylene, propane among others, – but in any case it means that it is a highly corrosive petrochemical. We soaked some film in it, as per the instructions on the manufacturer’s website. We used metal containers since the same instructions warned that Vitafilm can make otherwise sturdy plastics soft and squishy.

To cut the short story short, three months later we opened the can and ran some vinegar syndrome tests only to see that Vitafilm and/or the aliphatic petroleum hydrocarbon in it is snake oil: the levels of acetic acid which the film was emitting were the same as the ones it was emitting in May.

Wrapping it up

Film as an art form has been synchronized with the development of several industries, including the chemical one. Among the earliest film-related patents were not only cameras and lenses, but also film stock and various chemicals. Some of these were quite toxic and needed precaution. Others were pretty much ok. Acetate film itself, as far as my chemical knowledge goes, technically can be considered a bioplastic although the term was not around when this film stock was invented. Many of the chemicals used to maintain it, however, were toxic and could cause chemical burns and temporary respiratory issues. Old-school film-cement, for instance, used to edit film and bring shots together, made use of butanone, which is a petrochemical that we have in abundance only thanks to the oil industry.

And while it is true that we have moved to digital modes of producing and enjoying cinema, the classics of film, as well as the basic film grammar and the infrastructural set up of the studio system, were developed due to their more or less explicit ties to industrial chemistry.

With this I do not want to imply that we are guilty of something and should abandon film; neither I want to go in simplistic renderings of Marxist base/superstructure explorations of petropolitics and film aesthetics. By sharing my experience with film, I simply attempted to give another tactile and concrete expression to Zoë’s often-used metaphor: “We cannot unscramble the egg.”

We’re all in it in all kinds of unexpected ways and we should try and be conscious about it. But we are also all in it together, so no need to panic and don’t stop going to the movies!

End of part one of a two part series on toxic film. Tune in next time for an excursion in smell, cough, #MeToo, extractivism and recuperation.

要當醫生的原意我都知道但醫生的個性特徵沒聽說過。當醫生要心不是普通人的,膽子不是普通人的大,不怕血,不怕髒,不怕死人等, 誰怎這樣的勇敢呢?每天見到死人,病人,也看到血液和器官,誰可以 All Rights Reserved 2024 Theme: Fairy by arabuloku

Hi there terrific blog! Does running a blog like this require a large

amount of work? I have very little knowledge of

programming but I had been hoping to start my own blog soon. Anyway, should

you have any recommendations or techniques for new blog owners please share.

I know this is off subject nevertheless I just wanted to

ask. Many thanks!

Here is my webpage 온라인 슬롯

If some one wants expert view about blogging then i propose

him/her to go to see this webpage, Keep up the nice job.

Feel free to surf to my web site :: 카지노 게임 (mextbet.com)

Telf AG

es una simulacion economica de vanguardia creada por el equipo

de desarrollo de ArtDock Studio. Este juego da vida a

procesos complejos del mundo real y ofrece a los jugadores una experiencia unica de aprendizaje, analisis,

prevision y entretenimiento. La esencia del juego es ganar dinero e invertir,

mientras se le da al jugador libertad de eleccion en acciones y estrategia.

Saved as a favorite, I love your web site!

Review my web-site: Buy iOS Developer Accounts – VCCSturm.Com

I’m curious to find out what blog system you are utilizing?

I’m experiencing some minor security problems with my latest

site and I’d like to find something more safeguarded.

Do you have any suggestions?

Here is my website yohoho unblocked 76

Simply want to say your article is as astounding.

The clearness on your submit is just nice and that i could

assume you’re an expert on this subject. Well along with your permission allow me

to snatch your feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post.

Thank you a million and please keep up the gratifying work.

Here is my web site: https://carinsurancetips3.z20.web.core.windows.net/find-affordable-car-insurance-index-8.html

whoah this weblog is wonderful i like reading your articles.

Keep up the good work! You realize, a lot of individuals are searching around for this information, you could help them greatly.

Take a look at my web-site; Dhanbad escort service

Telf AG es una simulacion economica de

vanguardia creada por el equipo de desarrollo de ArtDock Studio.

Este juego da vida a procesos complejos del mundo real y ofrece a los jugadores una experiencia unica

de aprendizaje, analisis, prevision y entretenimiento.

La esencia del juego es ganar dinero e invertir, mientras se le da al jugador libertad de eleccion en acciones y estrategia.

Hey I know this is off topic but I was wondering if you knew of any widgets I could add to my blog that

automatically tweet my newest twitter updates.

I’ve been looking for a plug-in like this for quite some time and was hoping maybe you would have some experience with something

like this. Please let me know if you run into anything. I truly enjoy reading your blog and I look forward to your new updates.

my blog post गुदा समलैंगिक अश्लील

each time i used to read smaller articles or reviews which as well clear their

motive, and that is also happening with this article which I am reading here.

my web blog :: 온라인 슬롯

At this time it looks like WordPress is the best blogging platform

out there right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you are

using on your blog?

my blog – Selma

I am regular reader, how are you everybody?

This article posted at this web site is really good.

Feel free to surf to my web-site: دانلود آهنگ جدید زانکو

You really make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this topic to

be actually something that I think I would never understand.

It seems too complex and extremely broad for me. I am looking forward for your next

post, I’ll try to get the hang of it!

Feel free to visit my homepage :: Visakhapatnam escorts

Van insurance is actually essential for any person that relies upon their van for work or personal usage.

It provides financial security just in case of crashes or

even burglary, ensuring you are certainly not entrusted sizable costs.

Purchasing around for the very best Commercial van insurance insurance can assist you find a policy that matches your needs as well as spending plan. Don’t forget to match up the protection alternatives

delivered through different van insurance suppliers.

I do trust all the ideas you’ve offered on your post.

They’re very convincing and will definitely work. Still,

the posts are too short for novices. Could you please prolong them a bit

from subsequent time? Thank you for the post.

Stop by my site: آهنگ جدید حمید عسکری

An outstanding share! I’ve just forwarded this onto a coworker who had been doing a little homework on this.

And he in fact bought me breakfast due to the fact that I discovered

it for him… lol. So allow me to reword this….

Thanks for the meal!! But yeah, thanks for spending the

time to discuss this issue here on your blog.

Here is my web-site :: DEPOSIT QRIS

Howdy just wanted to give you a quick heads up.

The text in your article seem to be running off the screen in Safari.

I’m not sure if this is a formatting issue or something to do with browser compatibility but I figured I’d post to

let you know. The style and design look great though!

Hope you get the issue fixed soon. Many thanks

My web page – chirag delhi call girls service

I’m curious to find out what blog system you are working with?

I’m experiencing some small security problems with my

latest blog and I’d like to find something more safeguarded.

Do you have any suggestions?

my homepage :: آصف آریا

↑ dinsdale, ryan the lords of the fallen, sequel to lords of the fallen, https://ramblermails.com/ renamed lords of the fallen (неопр.).

This design is incredible! You most certainly know how to keep a reader entertained.

Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Wonderful

job. I really loved what you had to say, and more

than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

Visit my homepage; Събиране на трюфели

Замечательная информация!

Я впечатлён тем, как высокие ставки на спорт Украина на

спорт становятся всё более

популярными.

В последнее время я испытал несколько захватывающих игр на разных онлайн-платформ.

Что вы думаете о новых игр?

Я жду обмена мнениями!

Thank you for sharing your thoughts. I truly appreciate your efforts and I

am waiting for your further post thank you once again.

My blog; reduceri

Oh my goodness! Amazing article dude! Thanks, However I am

going through difficulties with your RSS. I don’t understand why I am unable

to subscribe to it. Is there anyone else getting similar RSS issues?

Anyone that knows the answer can you kindly respond?

Thanx!!

Also visit my web-site: SOSIAL TURNAMEN SLOT

Hi my family member! I want to say that this post

is amazing, nice written and come with approximately

all important infos. I would like to look extra posts like

this .

my site … آهنگ جدید سیام

Explore the finest Lahore Babes

escorts for high-class services.

Покрывать http://www.dachamania.ru/photo_gallrey/profile.php?uid=61368 каждый ярус теплоизоляцией.

Брусовые постройки экономичны,

долговечны.

hi!,I love your writing so so much! proportion we communicate extra approximately your

post on AOL? I require an expert on this space to resolve my problem.

May be that’s you! Taking a look ahead to look you.

My website :: 나루토카지노 먹튀